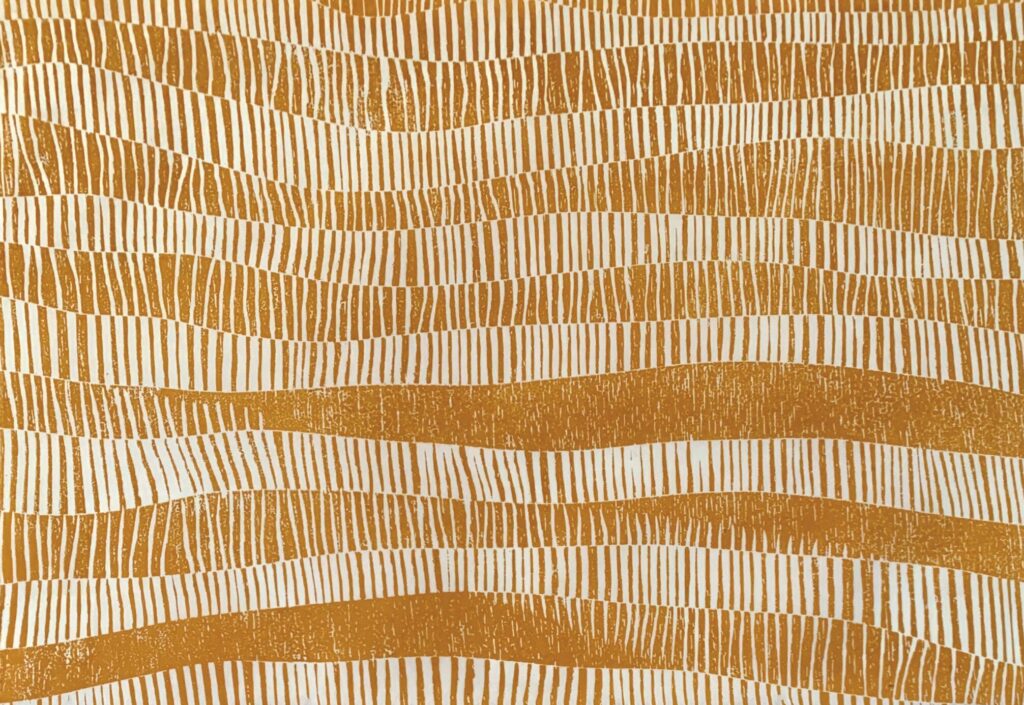

Image: Michelle Black | Golden harvest; Black soil plains II (detail) 2024 | Woodblock prints on Kozo paper; inked Black soil and intaglio collagraph plate; oil-based ink | 600mm x 500mm

2025 Western Downs Regional Artists Exhibition: Disrupt Curatorial Essay by Dr Sharna Barker

The 2025 Western Downs Regional Artists Exhibition invited artists in the region to consider the theme disrupt. The proposal is a provocation to question not only artistic traditions, but social, political, and technological structures and organisations. Indeed, to disrupt is to interrupt or destabilise a system, a way of living, and a sense of self. A disruption shifts perspectives or is a shakeup of routine and flow, provoking change. Globally and locally, we have experienced significant change and disruptions in recent years, and there is undoubtedly a sense and smell in the air of more change to come.

In the art world, to disrupt is a daring, rebellious act. It requires valour to create bold, original ideas or artworks that have an innovative impact and do not follow traditional rules. Historically, provocative artworks that have challenged audiences and expectations have done so through protest and activism, by engaging with ideas of the abject (repulsion and disgust), by testing boundaries or combining genres and mediums, and by challenging or rethinking narratives, to name a few.1 Here, we see artists question the limits of artistic conventions by using unruly actions or materials to detach from a system or fixed way of seeing and doing. As a result, artists push or overturn traditional methods of making, uncovering different outcomes, and sparking new conversations that move away from predictable approaches, or prompt us to think differently about understanding an idea, person, and place.

The artworks in this year’s exhibition approach the theme by asking what a disruption looks and feels like. Here, artists have used natural elements such as water, earth, fire, and wind as symbols or metaphors, juxtaposing binaries such as conceal and reveal, restriction and chaos, or life and death through layering, collage, distorting perceptions or viewpoints, and articulating personal stories where the body keeps the score, often invisibly, silently, and long-term.

For example, artists Jo Robertson, Jeannie Bowtell, Machelle Flanigan, Hannah Bean, Lisa Jayne Stiller, and Lauren Bensan each explore the rawness of the body and how disruptive experiences are anchored and carried within. The question of how to wear pain and how one might endure internal, unseen disruptions in daily life is evident in their works. Similarly, the psychological impact of disruptions appears in Sarah Davis’s paper and text-based collage, A victim impact statement, Charlie Mulligan’s self-portrait Repression, Shirley Makin’s Broken and We will remember them, and the evocative monster-like drawing What have I become? by Hallie Vickers. These ideas around self/body are further explored by evoking the viewer’s visceral reaction as seen in works by Regina Hyland, Katie Robertson, and Kristen Flynn. Here, the artists lean into themes of loss, death, decay, and transformation, as does Bill Perry’s Adam and Eve picnicking in paradise. In contrast, Melody Walker’s realistic painting Blessed Disruption and drawings by Meg Noack use emotional strategies of joy and humour to engage viewers, relying on their understanding of family dynamics.

Like Flynn and Mulligan, the use of collage and assemblage is apparent in the artworks of Cindy Grimes, Anna Moeba, Coralie Milne, Helen Druce, and Eileen Parker, who distort perspectives or reimagine ideas of reconstruction, connection, and care. Claudia Ehlers and Ariel Ehlers also apply collage and layering techniques to vocalise resistance—asking what disrupts them and how to reciprocate this disruption. In a similar vein, Carly Walker’s digital overlaying of fire and a poppy flower seeks to take a stand against acts of ruin and provoke change.

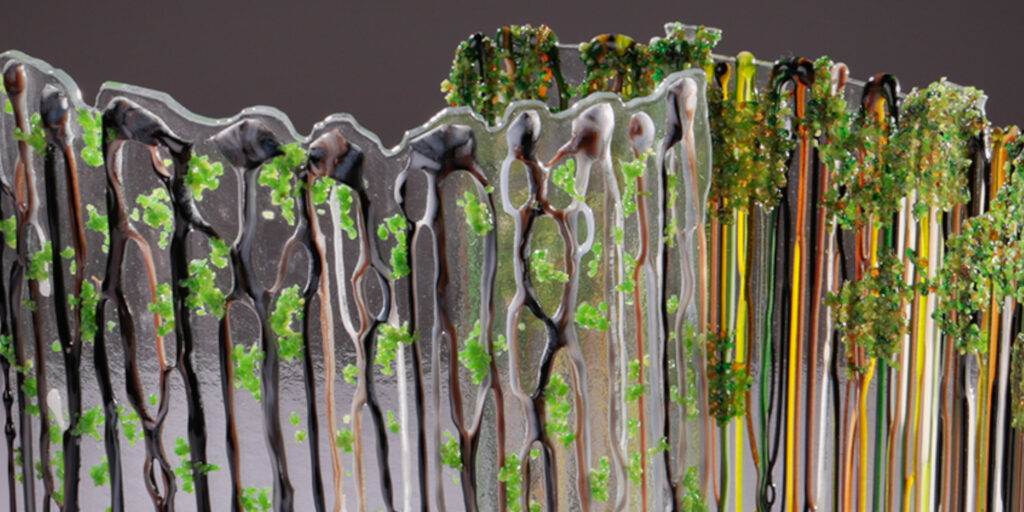

Artists Susie Nagy, Peter Van Der Veen, Meg Stevenson, Lucy Herd, and Patricia Hinz move away from the directly personal and instead find inspiration in the patterns and effects of water, wind, and earth, which evoke and symbolise the notion of disruption. Equally, Guy Breay’s Remnant, Michelle Black’s The Weight of Myall, Sharron Colley’s Shadow Rising, and Kay Vidler’s Riven Resilience explore the limits and potential of their chosen materials such as wood, ink, and clay, mindful of possible interruptions to the surface or structure. In contrast, Steve Cant’s sculpture intentionally suspends movement and form, skilfully balancing stability and instability. These examples highlight thoughtful consideration in making and underscore the concepts of failure, liminality, and precariousness that underpin the theme disrupt.

Navigating life’s unpredictability, rhythms, cycles, and shifts remains consistent across all works. Change is hard – it can be uncomfortable and demanding. Transitions require a certain level of investment and endurance. However, testing times play a vital, even valuable role in humanity. Perhaps the question is how we measure such value; how might a disruptive event or process shift from a negative or passive form to a positive and substantially productive condition?2 How do we respond to disturbances, and what can they offer in that moment and beyond?

The works in the exhibition show that hope, resilience, and transformation are inextricably linked to disruption. Indeed, antonyms of disruption include words like rebuild and repair. The artworks demonstrate that artists in regional communities are familiar with these ideas. Admittedly, I expected vulnerable stories of resilience and adaptability in difficult circumstances. Additionally, I wanted these expectations to be challenged.

What confronted me were highly emotional and empathetic responses to the theme. Such artworks activated my nervous system, destabilising me with provocative imagery and seeping, gritty shapes and textures of materials. Agitation or disarray in a viewer successfully reflects the topic, where the unsettling feeling persists long after leaving the gallery. I contend that artworks that make you question, think, and feel, or challenge the robotic mode of living, are revolutionary acts in a rapidly evolving world.